Who Are Palestinian Refugees?

Posted in: Society & culture

Since 1948, Palestinians have been subject to war, dispossession, and unjust policies, forcing many to live throughout the world as refugees. With limited resources and often difficult living conditions, the Palestinian people have faced much adversity and uncertainty over the years. Decades of conflict have hindered opportunities and development. Palestinians are the largest refugee group in the world, and the most enduring. Most are also stateless, adding yet another barrier to securing their rights and well-being.

It is impossible to understand who Palestinian refugees are without knowing something of the history of the 7 million Palestinian refugees, stretching across families, generations, and communities.

The experiences and circumstances of Palestinian refugees today are varied and diverse. Nonetheless, no matter how dispersed they may be, they remain connected through a common identity. “Behind every Palestinian there is a great general fact,” observed the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said — that he (or his ancestors) “once – and not so long ago – lived in a land of his own called Palestine, which is now no longer his homeland.”

Keep reading to learn more about why many Palestinians became refugees, where they were displaced to, and how Palestinians and their communities are doing today.

How Palestinians Became Refugees

Forced Displacement, Dispossession and Statelessness

Up until World War I, the land of Palestine was under rule of the Ottoman Empire, an Islamic power that was governed for centuries from the territory of present-day Turkey. Before the fall of the Ottomans at the end of the war, Palestinian people were citizens of the empire. When the war ended, the Middle East was exposed to the British and French colonial powers. The British were granted administrative control over Palestine by the League of Nations in 1920, under a post-World War One arrangement known as the mandate system that transferred control of former Ottoman and German territories to Great Britain, France and other nations. The British proceeded to lay the groundwork for establishing Mandate Palestine as a Jewish national homeland, without consulting the existing Arab population.

The devastating Holocaust during World War II and the mostly closed borders of many nations caused some 60,000 thousand Jewish refugees to flee to British-occupied Palestine. With tensions in Palestine on the rise, British forces prepared to vacate the region, leaving the Palestine question with the recently established United Nations. The UN proposed to partition “Palestine into two independent states, one Palestinian Arab [that would comprise some 44% of the land] and the other Jewish, with Jerusalem internationalized.” Only one of these states would come to be.

As soon as the British announced the end of their mandate in 1948, Jews in British Mandate Palestine declared their independence, establishing the state of Israel. The indigenous Palestinians and the neighboring Arab states rejected the partition plan as a denial of Palestinian sovereignty over the whole of Palestine. When Israel declared its independence, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon declared war on Israel in support of the Palestinian Arabs. These arrayed armies proved to be less formidable to the new Israeli state than may be expected, and most of them never crossed into the territories designated for Israel. As for the Palestinians themselves, with their irregular militias substantially weakened by prior conflicts in the preceding years, they were not a significant factor on the battlefields.

At the onset of war, Israeli forces launched a program of expulsion to depopulate Palestinian towns and villages throughout areas claimed for Israel, including Akka, Bir Al-Saba, Bisan, Lod (Lydda), Al-Majdal, Nazareth, Haifa, Ramle, Tabaria, Yaffa, and West Jerusalem, dispersing their populations outside of Jewish-claimed territory and claiming more than 78% of historic Palestine. Some 400 to 500 Palestinian villages were entirely depopulated and destroyed, while somewhere between 7,000 13,000 Palestinians were killed and roughly 750,000 Palestinians displaced from their homes, creating the first and largest wave of Palestinian refugees. This period is known to Palestinians as the Nakba, or ‘catastrophe.’

Displaced Palestinians and their descendants have been restricted or prohibited from returning to their homes ever since. Many relocated to Gaza or the West Bank, remaining within parts of historic Palestine, while others settled in the neighboring countries of Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.

Following their successes on the battlefield, Israeli forces expanded their control beyond the original partition boundaries and throughout most of historic Palestine, leaving Gaza and parts of the West Bank under Egyptian and Jordanian control respectively, and with no immediate prospects for the emergence of the Palestinian state envisaged by the United Nations.

The Second Wave of Refugees

Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1949, and the territory would remain under Jordanian control until 1967. Similarly, Egypt extended its authority over Gaza as a result of the 1948 war, and held it until forced to relinquish it to Israeli forces nearly two decades later.

Tensions simmered for two decades until 1967 when Israel noticed the buildup of pro-Palestinian Egyptian and Syrian forces along their borders. During a short-lived conflict, Israel launched a surprise air raid on these forces, taking possession of the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan, Gaza and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria. Several hundred thousand additional Palestinians fled their homes in these territories as a result of this war.

Palestinian Refugees under International Law

The World’s Most Protracted Refugee Crisis

Just as many Palestinians have endured political, social, and physical fragmentation, the legal standings that apply to them are similarly fragmented. Palestinian refugees did not settle in one place and instead ended up living under the varying and often restrictive legal statuses of different host countries. In 1948, as Palestinian refugees fled and were expelled from Israel, the international framework governing responses to refugee crises was not yet codified into its modern form. The United Nations only established the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 1950, and even then, the UNHCR was initially given a limited and geographically bound mandate primarily focused on Europe.

The historical circumstances that resulted in the creation of a distinct UN agency to provide relief to Palestinian refugees have also led to gaps in the treatment afforded to these refugees. Confusion around the status of Palestinian refugees under international law has sometimes resulted in Palestinian refugees receiving a lesser degree of protection from host governments.

After the violence around the 1948 conflict, Palestinians who remained within the borders of the newly formed state of Israel were given Israeli citizenship, but were placed under martial law for years to come as they were deemed a security threat.

A few years later, in 1952 Israel would enact its Nationality Law, which “barred the exiled Arab population from returning to the land as nationals,” making essentially stateless the majority of Palestinian Arabs who were previously Ottoman and, later, British Mandate citizens. Israel later passed a law that “criminalized the return of Palestinian refugees and authorized their imprisonment and re-expulsion.” (Unless otherwise noted, quotations throughout this piece are from Francesca Albanese and Lex Takkenberg, “Palestinian Refugees in International Law,” 2nd edition.)

As the population of Palestinian refugees continued to swell outside of the new Israeli state, the United Nations launched ad hoc relief efforts in coordination with NGOs to meet the growing humanitarian needs. At the end of 1948, the UN formed the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) to take charge of finding a solution to the ongoing situation in Palestine. However, the UNCCP foundered in the absence of a path forward to resolving the refugee crisis or establishing a comprehensive peace agreement between Israel and the Arab states.

In the face of the impasse, international efforts turned their attention toward delivering relief aid and economic development for the refugees, drawing inspiration in part from the model of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the US during the Great Depression. In December 1949, the UN established the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) to carry forward this assistance work with the 1948 refugees.

Establishment of UNRWA

To assist these fleeing populations, UNRWA began operations in 1950 with the mission of aiding “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period of June 1, 1946 to May 15, 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 [Arab-Israeli] conflict.” The new agency was formed to “prevent conditions of starvation and distress” among the refugees, as it had become apparent that they would not be permitted to return to their homes in the immediate future.

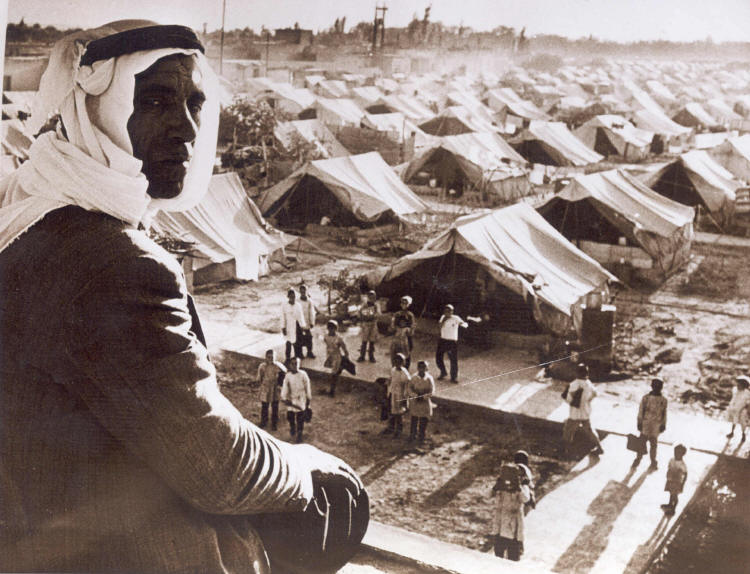

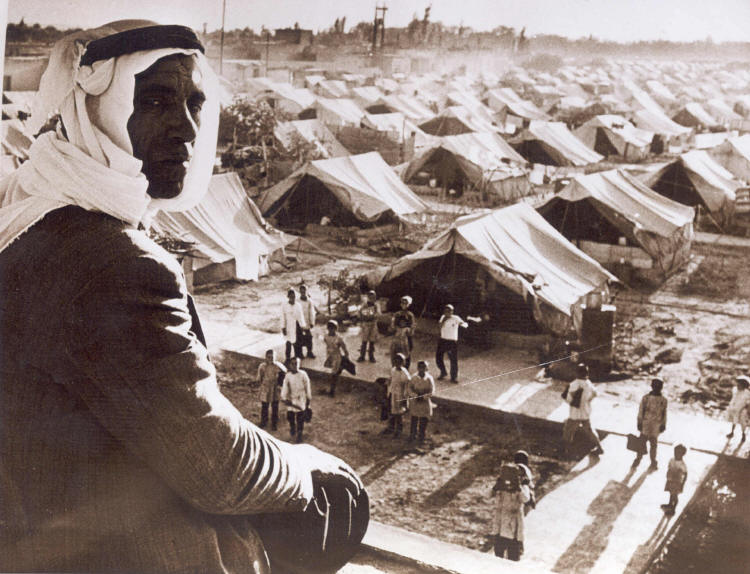

Acting as a subsidiary agency of the United Nations, with funding voluntarily provided by various countries around the world, UNRWA set up official refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. There are 58 official camps in total and approximately 1.5 million Palestinians live in these camps at present. Palestinians are the world’s longest-suffering group of refugees in the post-WWII era. The Palestinian refugees are “the largest and most enduring group of forced displaced of the post-Second World War era.”

At the time of their creation, these refugee camps were to accommodate some 750,000 displaced Palestinians. But, in 1965, UNRWA changed the eligibility requirements of a Palestinian refugee to include up to third-generation descendants of displaced Palestinian families. They expanded on this in 1982, by updating the requirements to include all descendants of Palestinians originally affected by the 1948 and subsequent wars. Currently there are around 5 million Palestinians eligible for UNRWA services.

What Is a Refugee?

“Every refugee needs a long term solution that will enable him or her to be integrated into society and to lead a normal life as a full-fledged member of a national community.” — UNHCR

The 1951 Geneva Convention addressing the status of refugees defines a refugee as a “person who, owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

UNHCR was created approximately a year after UNRWA was mandated to support displaced Palestinians. UNHCR was created in response to the post-war refugee crises in Europe but would evolve, particularly after 1967, into a global refugee response mechanism. In the 1951 Convention, the UN General Assembly gave UNHCR a mandate to “ensure that international protection is provided to refugees and durable solutions are found to ease their plight.” The formation of the UNHCR marked the first step in what would eventually become a more systematic global response to such crises.

Although UNRWA was typical of the ad hoc international approach to managing refugee crises that had prevailed until then, it is the only such entity still operating into the present day – a reflection of the exceptionally enduring nature of the Palestinian refugee situation.

These mandates are intended by the international community to complement each other to best support all refugees, including Palestinians. UNRWA provides direct services to Palestinian refugees but it is restricted from resettling Palestinian refugees, while UNHCR may resettle refugees (Palestinian refugees included, if they are outside of UNRWA’s mandated territories).

Similar to UNRWA, UNHCR’s Handbook on Procedures and Criteria also affords refugee status to all descendants and their future generations until their situation is resolved, ensuring that all affected refugee populations are accounted for. It is only when refugees are fully integrated into their new host societies and no longer need international protection, or are able to return to the country they fled, that they are no longer regarded as refugees. Sadly, the protracted nature of the situation facing Palestinian refugees is not unique — apart from its size and duration — some two-thirds of refugees worldwide are caught in similar states of unresolved stasis dragging on for many years.

The United Nations and international law have established a continuity of protection, at least in theory, for Palestinian refugees that provides social services and protection through UNRWA, in the countries where it operates, and through the UNHCR in other countries. In practice, many countries do not consistently acknowledge the applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention, that confers on Palestinians the same benefits and protections as accorded to other refugees. Nonetheless, UNHCR has not infrequently been called upon to serve Palestinian refugees, particularly since the 1980s, when many refugees fled the fighting in Lebanon for non-UNRWA countries.

Notably, UNRWA relies upon voluntary member state pledges, frequently resulting in funding shortfalls and making the social services available to Palestinian refugees tenuous. Albanese and Takkenberg observe that “funds remain largely inadequate to meet the need of increasing numbers of refugees.” The prolonged and intensely politicized nature of the situation facing Palestinian refugees also threatens their wellbeing and the prospects for a durable negotiated resolution of their plight.

Palestinians, like all refugees, will only be unburdened of their formal status as refugees when they manage to obtain national protection, either through voluntary return to their homeland or assimilation into another country. Despite many misconceptions to the contrary, international law is clear that the historic rights of the refugees are not dependent on their continuation of their status as refugees.

The resolution of refugee crises is a global responsibility. And in prolonged and seemingly intractable crises like that facing the Palestinians, sustained global engagement may be the only way to achieve resolution. One relatively new mechanism along these lines is the Global Compact on Refugees, adopted in 2018, which provides an international framework under the auspices of the UN for responding to refugee crises worldwide.

Where Did Palestinian Refugees Go?

Forced Displacement and Dispersal

Each major outbreak of war spurred massive waves of Palestinian displacement and exodus, ultimately displacing fully two-thirds of the population. Although some fled great distances, and away from the region, most Palestinian refugees don’t live far from their homeland. As of 2020, UNRWA lists the proportion of Palestinian refugees registered with the agency in its areas of operations as:

- About 40% live in Jordan

- Roughly 41% live in the West Bank and Gaza

- Nearly 19% reside in Lebanon and Syria

Of the Palestinians still living across historic Palestine, 43% are displaced refugees, including some 355,000 internally displaced Palestinians living in present-day Israel. The rest of the Palestinian refugee population and their subsequent generations have scattered throughout the globe, seeking refuge where they can.

Refugee Camps and Conditions

Many Palestinian refugees live permanently in temporary spaces that were established over 70 years ago. These camps have transformed over time from tent shelters to semi-permanent housing. Families cannot return to their homeland, and many have been trapped in a cycle of poverty and isolation.

Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon are often regarded as the worst of the region’s camps in terms of poverty, health, education and living conditions. Families crowded into what was designed as temporary housing have to cope with dense and narrow streets and alleys with open channels of sewage and loose piles of garbage. There are few clinics and hospitals to treat the sick. Tangles of exposed electrical wires often hang dangerously low over unlit alleyways, sometimes within reach of playing children. Deaths by electrocution are not uncommon. With staggering rates of joblessness, Palestinian refugees trying to improve their lives in Lebanon face restrictions and complicated formalities in the labor market. They are prohibited from working in most white collar professions.

In the last decade, some 50,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria fled the war there and settled in neighboring Lebanon. They were forced to find dwellings and compete for limited resources and services in already overcrowded camps.

Unlike in Lebanon, Palestinian refugees in the West Bank and Gaza face no distinct legal restrictions due to their status as refugees. However, here too, housing in the refugee camps is often cramped and substandard. And refugees must face the same challenging job market as other Palestinians. Indeed, 20% of displaced Palestinians living in the West Bank and more than half of the refugees in Gaza lack an income source, while 1.6 million are food insecure.

Outside of the Camps

Even at the outset, not all refugees from the violence of 1948 and in subsequent waves, have settled in UNRWA camps. Some found lodgings in towns or took shelter in informal gatherings.

Even within the countries where UNRWA operates, a significant number of Palestinian refugees also live outside the camps, sometimes in unofficial gatherings and settlements, but also integrated with host communities or concentrated in particular neighborhoods, or in informal gatherings.

Beginning in the 1950s and increasingly in the decades since, Palestinian refugees have also settled in countries further afield and outside of UNRWA’s remit. These new flights were driven by conflicts within their host countries and status restrictions on the refugees that significantly limited their ability to prosper.

Palestinians in Jordan

Unique among the major host countries of Palestinian refugees, most Palestinians in Jordan have been granted citizenship. Their numbers are significant, with Palestinians comprising upwards of 40% of all Jordanian citizens.

For the more than 2 million Palestinian refugees living in Jordan, their legal statuses vary based on where they came from and when they arrived in Jordan. Citizenship was first granted to Palestinians in 1949 with an amendment to the British Mandate’s Nationality Law of 1928.

Those who arrived in 1948 and from the West Bank in 1967 are citizens. Other Palestinian refugee groups like those who fled from Gaza in 1967 (including 1948 refugees registered with UNRWA) and other Palestinians who arrived later from Iraq and Syria are considered foreigners. Jordan grants these refugees travel documents and they can access many social services, but must pay for them at the higher rates billed to foreigners.

There are 10 Palestinian refugee camps as well as several informal gatherings in Jordan, although less than a fifth of Palestinian refugees are registered in these camps.

Those from the West Bank, including refugees, who sought residence in Jordan after 1988 are also considered foreigners and are not eligible for Jordanian citizenship.

In 1988, Jordan revoked Jordanian citizenship from those living in the West Bank by amending the Nationality Law of 1954, leaving some 1 million Palestinians stateless. Hereafter West Bank Palestinians were eligible only for temporary passports from Jordan. These passports were issued in the form of a green card, limiting West Bank Palestinians to residing in Jordan for no more than 30 days.

Palestinians in Lebanon

Lebanon has the highest percentage of Palestinian refugees living in abject poverty. Due to harsh living conditions and restrictions, more than half of the original refugee population has left Lebanon over the last 70 years.

The largest arrival of Palestinians in Lebanon occurred in 1948, with some 100,000 Palestinians fleeing to villages and what became refugee camps in Lebanon. Other notable groups of Palestinians also fled to Lebanon from Gaza after the Suez Canal crisis in 1956 and after the 1967 war. Several thousands arrived from Jordan in the 1970s after clashes between Palestinians and Jordanians, and close to 40,000 fled from the civil war in Syria beginning in 2011.

The first group of Palestinians who arrived in Lebanon were generally welcomed. Although most were never integrated into Lebanese society like in Jordan and Syria, they were registered with UNRWA and were considered legal residents, having access to some freedom of movement and employment opportunities. Some Lebanese citizenships were granted during this time, but only to those with familial connections. Their fortunes worsened after 1958 when a change in government brought new policies that increasingly marginalized and impoverished the refugees.

Lebanon’s system of apportioning government seats based on religious groupings has traditionally made demographic shifts very politically sensitive. Opening the door to citizenship for the large Palestinian refugee population, which would significantly impact the religious demographic balance, has therefore long been considered politically impossible.

As in other Arab host countries, with the exception of Jordan, the (incorrect, at least in legal terms) perception that granting citizenship to Palestinian refugees would undermine their right to voluntary repatriation to their historic homeland is also frequently cited as a motivation for barring refugees from integration into the host society.

For Palestinian refugees, naturalization in Lebanon is very rarely an option. And although they are granted residency, their treatment is inferior to that of other foreigners.

The second group of Palestinians are those not registered with UNRWA. This group consists of Palestinians who either fall just outside of UNRWA eligibility requirements, live just outside of UNRWA mandated territory, or arrived in Lebanon after 1948. This group was also granted legal residency in Lebanon and are treated similarly to those registered with UNRWA, but their residency expires sooner than the first group of Palestinians.

Other groups of Palestinians consist of those not registered with the Lebanese government or UNRWA, and who are therefore undocumented, and those from Syria. After 2011, several tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees from Syria fled the civil war there by crossing the border into Lebanon. These doubly displaced refugees lived in grave scarcity as one of the poorest groups in Lebanon. Both groups face the harshest of restrictions. UNRWA offers some basic services to Palestinians of these groups even if they are not registered with UNRWA. They attempt to stay under the radar, relegated to seeking under the table work or other irregular sources of income.

Since they are legally regarded as foreigners, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are generally restricted from accessing public benefits. They are explicitly forbidden from employment in dozens of professions, including in many of the most lucrative and high status fields like medicine and law.

Due to the many restrictions Lebanon places on Palestinian refugees that severely constrict many aspects of daily life, the periods of violent conflict over the decades, and a recent sharp downturn in economic conditions in Lebanon, a great many of the refugees registered in Lebanon have actually left the country.

While some 450,000 Palestinian refugees are registered with UNRWA in Lebanon, the actual number of residents is believed to be closer to 250,000. Indeed, most of the Palestinians that have resettled in Europe in the last few decades came from Lebanon.

UNRWA maintains 12 refugee camps across Lebanon that are home to many of the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Residents of the camps are often restricted by the authorities in their ability to come and go from the camps. Palestinian refugees also live in towns and informal gatherings. Living conditions are generally poor. The “camps and gatherings are overcrowded, severely underserviced, and generally unhealthy,” Albanese and Takkenberg note.

Palestinians in Syria

Prior to the outbreak of civil war in Syria in 2011, some 560,000 Palestinian refugees registered with UNWRA were relatively well integrated into Syrian society. Seen as an aid to the country’s development, Palestinian refugees were generally welcome, even if they were not able to become formally naturalized as Syrian citizens.

About 75,000 refugees entered Syria in flight from the violence in Palestine in 1948. These first refugees were joined by 16,000 more in 1967, as well as by several smaller influxes.

Similar to Lebanon, Palestinian refugees in Syria were classified into groups determined by their registration status with UNRWA and the Syrian government. Groups of refugees arriving before 1956 are all registered with the Syrian government. Of this group, those displaced from the violence of 1948 also fell under UNRWA eligibility and after 1991 this eligibility expanded.

UNRWA operated nine refugee camps, in addition to four informal camp gatherings.

Prior to the Syrian war, those registered with Syria became legal residents and granted provisional residence cards valid for six years. Those registered with UNRWA additionally had access to basic health and education services. Palestinian refugees in these categories were treated almost the same as Syrian citizens – those registered with Syria accessed employment, education, healthcare, and other necessities.

A smaller group of 10,000-15,000 refugees in Syria were not registered with either Syria or UNRWA, allotting them fewer legal support. These groups of Palestinian refugees arrived primarily in 1967, and in 2003 after the war in Iraq. They are restricted from basic rights like residence permits, healthcare, and education. And they also need to apply for work permits.

The civil war that started in August 2011 has harshly impacted Palestinian refugees living in Syria. Palestinian camps and gatherings were often sites of hostilities and attacks. Violence and threats of violence were directed at the refugees by both the government and armed opposition groups. The prospect of conscription into the military provided another impetus for flight. By 2018, only 438,000 Palestinian refugees were still in the country, with most of these (60%) internally displaced by the fighting.

Along with over 5 million Syrian refugees, there were around 120,000 Palestinian refugees who fled the country in search of safety for their families. For some, this journey took them to Europe by boat, a highly treacherous journey, while others crowded into UNRWA camps in Lebanon, Jordan, Gaza, and the West Bank, undergoing their second or third displacement, in many cases.

Palestinian Refugees in Palestine

Although Palestine symbolically declared independence in 1988 and was granted observer status at the United Nations in 2012, it lacks sovereignty or the ability to exercise many of the protective functions of a state. For this reason, international legal authorities continue to regard the 2 million Palestinian refugees living in Gaza and the West Bank as refugees and stateless persons.

The demographics of Gaza were completely transformed by the wars of the 20th century. Some four-fifths of the population in Gaza are refugees (1.4 million people) from other parts of historic Palestine. Gaza hosts eight Palestinian refugee camps, all established in 1948 and 1949, in the aftermath of the Arab-Israel War. But poverty, overcrowding, an absence of urban planning, unemployment, and a lack of school and public infrastructure make daily life challenging for the roughly 600,000 people who live in the camps.

According to UNRWA, 871,000 registered Palestine refugees live in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, making up approximately 15 percent of all Palestine refugees worldwide. About one-quarter of them live in the 19 refugee camps, while most of the remaining refugees reside in West Bank towns and villages. Many of those who live in towns often reside near the camps.

The refugee camps in the West Bank are often subjected to heightened levels of violent conflict with Israeli forces, which regard them as centers of militancy.

Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem, refugees or not, live under a different administrative system than that prevailing in other parts of the West Bank. Israel regards East Jerusalem Palestinians as permanent residents, with the option to apply for citizenship, although these applications are frequently rejected. Their residency status is vulnerable to revocation for various reasons.

Palestinians, refugees included, in the West Bank and Gaza generally are sharply restricted in their movements between the two territories (and with Israel), with permits only granted for exceptional circumstances. Like other residents in the occupied territories, the refugees are participate in legislative and presidential elections under the administration of the Palestinian authorities. Palestinian refugees in the West Bank and Gaza have the same legal status as non-refugees, although refugees have reported discrimination in informal contexts as a problem in the West Bank. And residents of the camps in Gaza and the West Bank are more likely than those outside the camps to be stuck in substandard housing.

While the West Bank has the highest number of Palestine refugee camps, they tend to have smaller populations than other Palestinian camps located in Gaza, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria. However, they too face serious issues with overcrowding and limited resources.

Where and how are they now?

Palestine: a Nation in Exile

Many millions of Palestinian refugees live outside of their homeland, awaiting a durable negotiated solution to their plight. As products of the most enduring post-World War II mass displacement crisis, most are second, third, or even fourth generation refugees, whose ancestors fled the violence of 1948 or later hostilities.

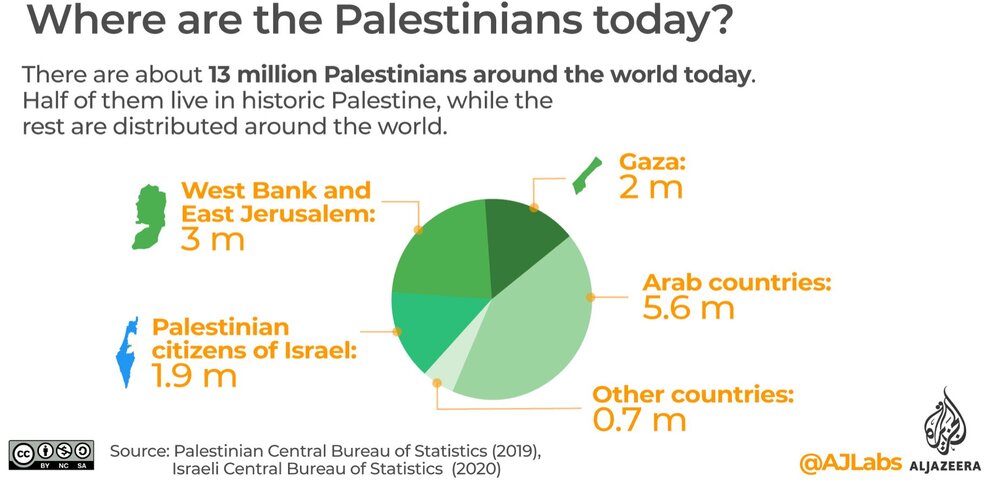

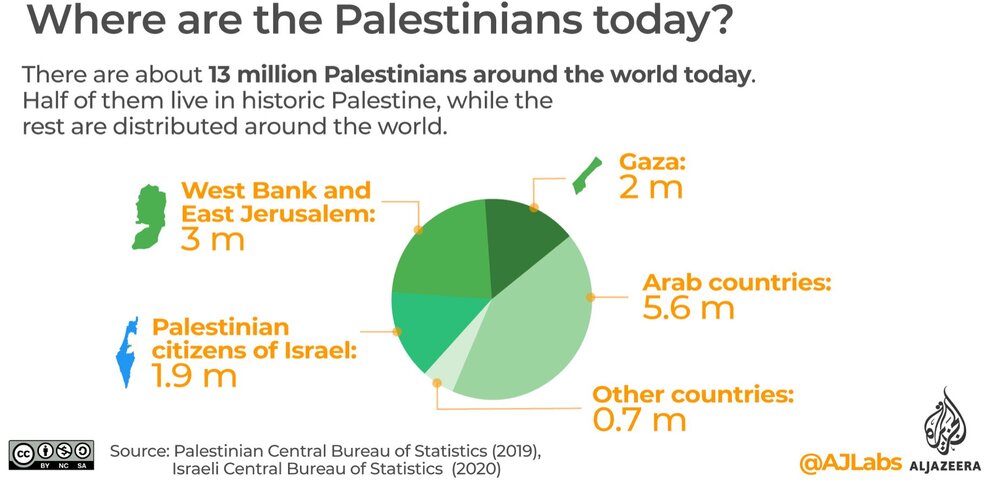

Of the 13 million Palestinians worldwide, less than 7 million live in Israel/Palestine. They share a powerful common identity, but live in widely varied circumstances. The diversity of Palestinians’ experiences is reflected in local identity, living conditions, economic standing, educational experiences, and much more. Some 33% of Palestinian refugees still live in UNRWA’s camps in Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria. The remaining two-thirds live outside of the camps in those countries or have migrated elsewhere, including to the Americas, Europe and the Gulf countries.

Owing to upheaval in their host countries, many refugees from Palestine — perhaps 700,000 in all — have been subsequently subjected to yet more displacement over the decades. Having started new lives in Syria, Kuwait, Iraq, Lebanon, and Libya, conflicts in these countries forced them to flee again.

Approximately 11 million Palestinians live in the Middle East and North Africa, with about 5 million residing in Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and 6 million in other countries in the region.

Beyond the countries covered by UNRWA, Egypt is also home a significant population of some 70,000 Palestinian refugees. They are considered foreigners by the state and, although the community is mostly impoverished, the authorities prevent them from accessing UNHCR services and protection. Another roughly 900,000 Palestinians live in the Gulf countries, most of whom migrated there to take advantage of greater economic opportunities.

Turmoil has plagued many of the countries in the Middle East and North Africa where Palestinians settled and many of these refugees, totaling some 700,000 people, were forced to uproot their lives once again to seek new countries of refuge.

Beyond the Arab nations, there are sizable Palestinian communities in Europe, especially in Germany and Sweden, and in the Americas, particularly in Chile, Honduras, and the US.

Chile is home to the largest population of Palestinians outside of the Arab world. Many Palestinians in Latin America first arrived in the late 19th and early 20th century, to avoid being drafted into the Ottoman military or in pursuit of economic opportunities. These Palestinian immigrants tended to be mostly Christian.

Ongoing Displacement Threats

Within the West Bank and Gaza, refugees and non-refugees alike live with extensive restrictions and under Israeli control. In the West Bank and East Jerusalem, displacements are the result of Israeli policies to revoke residency permits, the direct clearing of informal gatherings, and the denial of building permits enforced through home demolitions. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the Occupied Palestinian Territory describes a situation of “continuous and continued forced displacement of Palestinians, including refugees” in the West Bank.

In Gaza, military operations, especially during periods of escalation, have destroyed many housing units, internally displacing hundreds of thousands of people, many of them already refugees from the 1948 war.

The Contributions of Palestinian Refugees

Palestinian refugees the world over have made significant contributions to their communities. They are educators, philosophers, artists, entrepreneurs, managers, laborers, humanitarians, farmers, comedians, executives, doctors, and much more. Some have achieved international fame – like the professor and intellectual Edward Said, poet Naomi Shihab Nye and comedian Mo Amer – but most Palestinians are simply woven into the fabric of our societies, getting on with their work and lives.

We are lucky at Anera to have built a community that has brought Palestinians together from dozens of countries. We are also proud to partner with local organizations in Palestinian refugee camps across Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan. Most of what Anera does would not be possible without the work that Palestinian refugees are doing in their own communities.

Palestinians Speak

When putting this post together, Anera reached out to our network of supporters to tell us their stories and what it means to be a Palestinian refugee. These are some of their responses:

Suzy Zaky – My dad (born 1946) was carried out of Gimzu on my grandfather’s shoulders in 1948. They settled in tents and eventually made their way to Areeha, then Amman, Jordan. My dad came to the US in the 70s and I was born here in 1979. My grandfather and his generation, my father and his generation, myself and my generation and my children are all Palestinian refugees…

[Being a Palestinian refugee] means you feel simultaneously blessed to be American and safe and in a land that gave you so much opportunity, but also feel a piece of your identity is missing and there is a constant ache to return to the land of your origin that cannot be fulfilled.

Fares Awwad – I believe that every Palestinian who lives outside of Palestine (the whole Palestine) and irrespective of age, generation or social status is a refugee. None of us had the choice to be where we are had it not [been] for the Israeli occupation. As such, yes, I consider myself as a refugee. Both of my parents were born in Palestine (Lidda and Yafa) before the 1948 occupation and they were only children when they and their families were forced out back then. They settled in Jordan and established their lives there but never lost their Palestinian identity and embedded it in their children.

[Being a Palestinian refugee] feels that something is lost… Loss of privacy, identity, and even freedom. I, for one, have never visited Palestine (yet want to dearly) but identify with everything that is Palestinian on all levels. The faintest smell of olive oil from Palestine, the aroma of a musakhan meal or even that of Nabulsi soap give the feeling of joyful pride of being originally from that land.

Ibtissam Rizkallah – I was born in Haifa, Palestine. My parents took refuge in Lebanon in 1948. My dad worked as a truck driver for UNRWA in Beirut. My sister and I went to the Baptist hospital school of nursing in Gaza, with the assistance of UNRWA. With their help, and the degree we received, we were able to help our parents and later live in the USA. I passed the nursing board exam and worked for 30 years until retirement.

[Being a Palestinian refugee] means the world to me. I am a very proud Palestinian — proud of my roots, my history, my ancestry, my language, my fellow Palestinians who are still fighting to keep our history alive by teaching our children and grandchildren about Palestine and our heritage. Long live Palestine!

Nina Abdul Razzak – My family are originally from the village of Amqa’a in the city of Akka. In 1948, my father, who was only four years old then, was carried out on the shoulders of his eldest brother, who was then 20 years old. Together with their sister, parents, and extended family, they fled on foot to the borders of Lebanon. After that, they settled in Lebanon, namely in an old and shabby part of Beirut, but not in a refugee camp. My mom’s parents also come from Amqa’a and they too fled in 1948 to Lebanon. But my mom was born one year after in the South of Lebanon and she and her parents settled after that in Ein El Hilweh refugee camp.

After my parents got married, they lived in Beirut for a few years and then my dad, who had graduated from the American University of Beirut as a gynecologist in 1973, found a job in a hospital in Saudi Arabia. He worked in KSA for 25 years, brought us up and educated us. Then he retired and went back to Lebanon. In Lebanon, he worked at the UNRWA Al-Hamshari hospital in Sidon as Chief of Gynecology and Obstetrics. His work was more like a voluntary basis, as he was only getting peanuts as payment. But he did not care. All that mattered to him was that he was serving and helping his people.

As a refugee, one always feels unwelcome, looked down upon, and considered as a burden on the host country. There is always that constant emptiness one feels, like a hole in one’s heart, because we know we are missing something vital, mainly HOME. The yearning therefore never stops…there is also a feeling of guilt one feels for not being able to serve in his/her own country. This feeling is particular to educated people I believe who know that they are doing a lot of service in the world but it is not directly impacting their own people. As an educator, many times I wish I could be in Palestine teaching in a university and benefiting Palestinian students through my knowledge and skills that I was lucky to develop by studying abroad and gaining international exposure.

Dr. Abdallah M. Isa – My family came from a little town, Galilee, right at the border with Lebanon. We were kicked out from our homes by Jewish militias who were shooting at us. We climbed the mountain separating Palestine from Lebanon, hiding behind boulders to avoid being hit by Jewish machine gun fire. I was eight years old at the time. We settled, at the beginning, in a little Lebanese village, Tair Harfa, living there for six months before moving to Beirut. When I talk about my family, I mean my two sisters, as both of our parents were dead. I enrolled at the American University of Beirut in 1955 and graduated with a B.S. degree. Then I enrolled at the University of California-Berkeley and the University of California Medical Center in San Francisco, graduating as a doctor in 1968. After specializing in immunology and infectious diseases, I joined the medical school faculty in Nashville, Tennessee.

Joan Rashid – My husband was a Palestinian refugee. His village, about 12 miles from Jerusalem (Deir Aban), was destroyed and his family forced to flee to Beit Jala. He was only 12. After they used all their money and sold the animals they took with them in trucks, they spent many years in refugee camps. They suffered and he had to support his parents and siblings instead of going to college. The effects of this on his life and the lives of others was tremendous and impacted our marriage, life, and was a source of lifelong grief for him (and me). He has been deceased for 10 years now.

[Being a Palestinian refugee means] lifelong suffering, grief, bitterness and losses.

Dounia Iskanda – [Being a Palestinian refugee] represents heritage. We still hold onto all the documents we had, as old as from the 1920s. It represents strength, resilience and most importantly presence. Presence is rather important because it’s the only thing we have, our presence is a case by itself. Anyone who wants to argue against the Palestinian cause, all I have to do is present myself not only as a human, but also a case.

Iyad Omar – [Being a Palestinian refugee] means that I have no rights in Lebanon to work. I faced this a lot after my graduation from university. I can’t get legal papers proving I’m an engineer to enter the engineers’ syndicate. I can’t possess land to build my own house on it, I don’t have any rights to work or to live a dignified life. I don’t have a medical coverage from the ministry and 95% of companies don’t want a Palestinian working for them. I was born in Lebanon but am treated like a foreigner.

How You Can Show Solidarity With Palestinian Refugees

As the largest stateless population in the world, Palestinian refugees lack the protection of a state, making international support from individuals and civil society all the more important. With ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and the hardships Palestinian refugees confront there every day, you may be wondering what you can do to help. There are many ways you can be engaged and offer support.

Learn and Share

From movies and literature to blogs and informative news sources, there is a lot of information about Palestine and the current situation. We have put together a short list of our favorites. Whether you’re just getting started or have worked in Palestine for years, we hope there’s something for you in this list to inspire you to learn and explore further.

Read more about the lives and accomplishments of more Palestinian refugees on Anera’s Tapestry of Humanity.

Tap into some Palestinian advocacy-oriented organizations

What Anera does as a non-political, non-sectarian humanitarian organization happens in parallel with what other worthy organizations are doing. We therefore share this list of some nonprofits that are engaged in other aspects of work in and for Palestine.

Get Involved With Anera

For over 50 years, Anera has helped Palestinian refugees by building on the resilience that lives within the hundreds of vulnerable communities we reach. This is because we believe that each person, no matter their circumstances, embodies promise and that people with hope can shape the life of their families, their neighborhoods, and their region.

Be sure to follow and share Anera’s work on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter channels.

Please also consider making a donation. Anera provides immediate and sustainable relief to Palestinian refugees and other vulnerable communities in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, and Jordan. We build infrastructure, train teachers, teach job skills and basic literacy and math to youth, lead sporting activities, deliver vital medicines, link homes to water, and much more.

Except where other sources are given, this piece is primarily based on Francesca P. Albanese, Lex Takkenberg, “Palestinian Refugees in International Law,” Oxford UP, 2021.

OUR BLOG

Related

Joint Statement 200+ NGOs call for immediate action to end the deadly Israeli distribution scheme (including the so-called Gaza Humanitarian Foundation) in Gaza, revert to the existing UN-led coordination mechanisms, and lift the Israeli government’s blockade on aid and commercial…