May, 2025

A story of illness, displacement, survival and waiting

In one of the narrow alleys of tents sheltering the displaced in Mawasi, Khan Younis, in the southern Gaza Strip, 66-year-old Hajj Amer walks slowly.

Amer carries little from his long years of life except a yearning for the home he was forced to twice flee, and the honorific title of "Hajj" earned through his wisdom and patience in the face of pain.

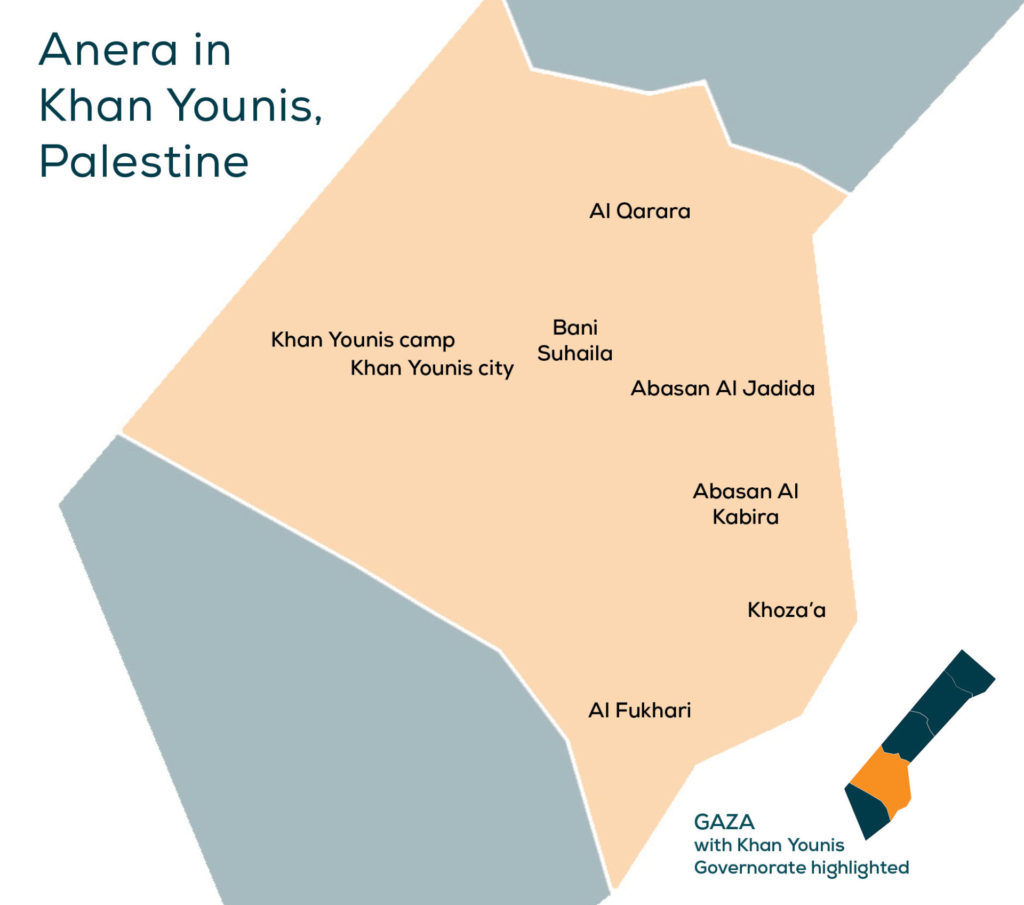

He used to live in Qizan al-Najjar, in the east of the Khan Younis governorate, where he led a simple life.

He was forced to flee after the outbreak of the war in 2023. After the ceasefire was reached in late January, he returned to his home. But the renewed warfare once again pushed him into displacement, returning him to the tents of Mawasi where he had once spent a year and a half. It is a place where stories of suffering repeat, spaces shrink, and pain grows, especially since the war restarted on March 18.

"I never thought I’d see a time when feeding my grandchildren would become this painful, this uncertain.”

Displacement comes at uncountable costs

Since October 7, 2023, the eastern parts of Khan Younis have been subjected to relentless bombing, forcing tens of thousands to flee. Qizan al-Najjar was among the hardest-hit areas during the first phase of the war.

Hajj Amer describes his home as more than just a shelter.

“My house has six floors, built over many long years with my ten sons,” he says, while sitting in the waiting line at the Anera field clinic established in Mawasi.

His home once housed his entire extended family — married children and over twenty-seven grandchildren. But they were forced to evacuate within the first week of the war, on October 13, 2023, as the bombing intensified nearby.

He and his family spent a year and a half in the Mawasi tents — “an indescribable suffering,” he says.

“We were overwhelmed with joy," when a ceasefire was announced on January 19. "We returned home immediately,” he says. “Luckily, the building was still standing, though hit by several shells.”

“We tried to repair what we could, but we barely had time to rest before the war returned again,” he says.

“The war resumed just a day after Eid. We were forced to evacuate once again. And here I am — back in a tent, as if I never built a home or worked hard to fix it,” he says with emotion in his voice.

He describes the forced evacuation not just as the loss of a building, but the loss of everything that made him feel safe.

“Six apartments, each housing a family, each with children, furniture, life. We left everything behind, took only what we could carry, and left in tents."

"The only joy I felt was when we returned home — but now it’s gone again, with the fear of it being bombed once more."

Tent life is not a life

As the war dragged on and temporary ceasefires collapsed, life in the camps became even more unbearable. Thousands of families were left without gas, electricity, or clean water, forced to survive in primitive conditions.

Today, Amer and his family live in crowded tents in Mawasi with no privacy, comfort, or stability.

“To go from my big home to a single tent... I can’t sleep at night. My wife has a lung condition and can’t tolerate the smoke from the fire. I don’t know what to do,” he says.

“We never expected the war to return, nor to be displaced again,” he says bitterly. “The most painful moment was having to flee once more and return to life in tents.”

"I used to work in construction, lifting heavy stones and cement. Now I can’t even stand."

He describes the tent conditions: freezing at night and unbearably hot during the day — completely unsuitable for his age and health, and his 60-year-old wife, Naima.

“At this age, we need comfort and stability — not this harsh life. How can we run fleeing from one place to another when danger approaches? We just don’t have the strength anymore.”

What worsens his conditions is the severe food crisis in Gaza that has reached catastrophic levels, with families surviving on canned goods and scarce items sold at exorbitant prices.

Access to fresh food is nearly impossible amid the ongoing siege, displacement, and market collapse.

"We barely have anything to eat. We live on canned food and whatever little we can find in the market—if it even exists,” he says.

“Prices are unbelievably high. Sometimes we go days without fresh bread or vegetables. I never thought I’d see a time when feeding my grandchildren would become this painful, this uncertain.”

“Sometimes we go to five pharmacies and find nothing—not even a single pill."

When asked if he remembers any happy moment during the war, Hajj Amer says bluntly:

“I can’t recall a single happy moment. The only joy I felt was when we returned home — but now it’s gone again, with the fear of it being bombed once more.”

“If it weren’t for clinics like Anera’s, many would’ve died.”

Anera's Healthcare Centers Offer A Lifeline

As the siege and war continue, Gaza’s health facilities are struggling to provide services and basic medications. People with chronic conditions like Hajj Amer are left untreated in unlivable environments — no electricity, no refrigeration.

In this medical collapse, Anera’s mobile clinics have become a rare lifeline. The clinic features here is one of several receiving emergency support from Americares to continue providing critical health services.

For Amer, who suffers from chronic illnesses, the field clinic brought hope.

During the war, Amer has battled more than bombs and displacement. He suffers from diabetes, high blood pressure, varicose veins, a spinal disc injury, and open diabetic wounds on his right leg.

“I’ve had diabetes for 40 years. I used to work in construction, lifting heavy stones and cement. Now I can’t even stand. The pain doesn’t leave me. My wounds won’t heal.”

He says his condition is severe due to the combination of diseases — but he finds relief in the care he receives at the Anera clinic.

For the past seven months, Amer has visited the clinic regularly, where a specialized medical team monitors his case, treats his wounds, and provides essential medications.

“My blood sugar was 400, now it’s 120. My blood pressure was 360, now it’s 179. Thank God for Anera’s clinic.”

A blood sugar level of 250 milligrams per deciliter or above is considered hyperglycemic and dangerously elevated.

“They change my bandages every two days. They give me medicine for pressure, diabetes, antibiotics for my leg, even painkillers.”

“The chronic diabetic wound in my leg used to be infected, but here they treat it regularly. Everything I need is available.”

What impresses him most is the kindness of the staff and their relentless effort to source rare medications.

“Today, I received an antibiotic for my wound and Glucophage 1000 [generic name: metformin — an oral diabetes medicine that helps control blood sugar levels] for my diabetes, among other meds.”

A life partner in love and pain

For Hajj Amer, life during the war amid so many hardships has led him to a new appreciation of his marriage.

“This war taught us the value of the simplest things. We lost everything. Now all we want is peace and safety.”

Hajj Amer says he's come to realize during the war just how deeply he relies upon his wife.

“I deeply respect her — she’s been my pillar through all of this," he says.

“She’s my life partner. She stands by me in everything and eases my pain. She never fell short — not for me, not for her children.”

Despite her age, since the war his wife has had to fetch firewood, cook over open flames, and look after their children and grandchildren.

“I worry so much about her health. A woman her age deserves comfort and peace, not this endless hardship,” he laments.

“Even Anera doesn’t have insulin anymore. Pharmacies are completely out. I have only two vials left.”

Medication Shortages Leave Thousands in Agony

Since the war began, Gaza has been under a tighter form of the blockade imposed since 2007, cutting off medicine and supplies. After a brief respite in late January and February of this year, Israel imposed a total blockade on all cargo on March 2. Thousands—especially those with chronic conditions—have suffered in silence.

Delays and shortages have led to amputations, comas, and even death.

“Sometimes we go to five pharmacies and find nothing—not even a single pill. Insulin is gone unless you find it on the black market at outrageous prices. And if I can’t afford it, I endure the pain.”

“The shelves are empty. People are suffering. I’ve seen patients with gangrene, uncontrolled diabetes, and severe infections.”

“If it weren’t for clinics like Anera’s, many would’ve died.”

Amer’s greatest fear is the total cut-off of medications — especially with crossings closed for over 50 days.

“Even Anera doesn’t have insulin anymore. Pharmacies are completely out. I have only two vials left.”

“If insulin runs out, I’ll suffer. And many chronic patients will suffer too.”

“We want to live with dignity. My children and grandchildren did nothing to deserve this. Why should they bear all this pain?”

As the war drags on and the blockade continues, the basic supplies that sustain life are dwindling. Appeals to the UN and international bodies are desperate pleas from a collapsing society.

“International organizations must increase support,” Hajj Amer says.

“We’re not asking for luxury — just for medicine, injections, clean bandages. Organizations must reach the camps, the tents — not just the big centers.”

“Clinics like Anera are our lifeline. All organizations must work like them. Without medicine and food, people die. And we’re tired of dying every single day.”

Despite everything, Amer still clings to hope and his right to live in dignity.

“We want to live — like any other people. Not a tent life. Not waiting in line for medicine. Not humiliation. We want to live with dignity. My children and grandchildren did nothing to deserve this. Why should they bear all this pain?”

He ends with a plea: “Enough wars. Enough pain. Open the crossings. We are human beings. We want to live, not get used to dying. Show us respect.”