May, 2025

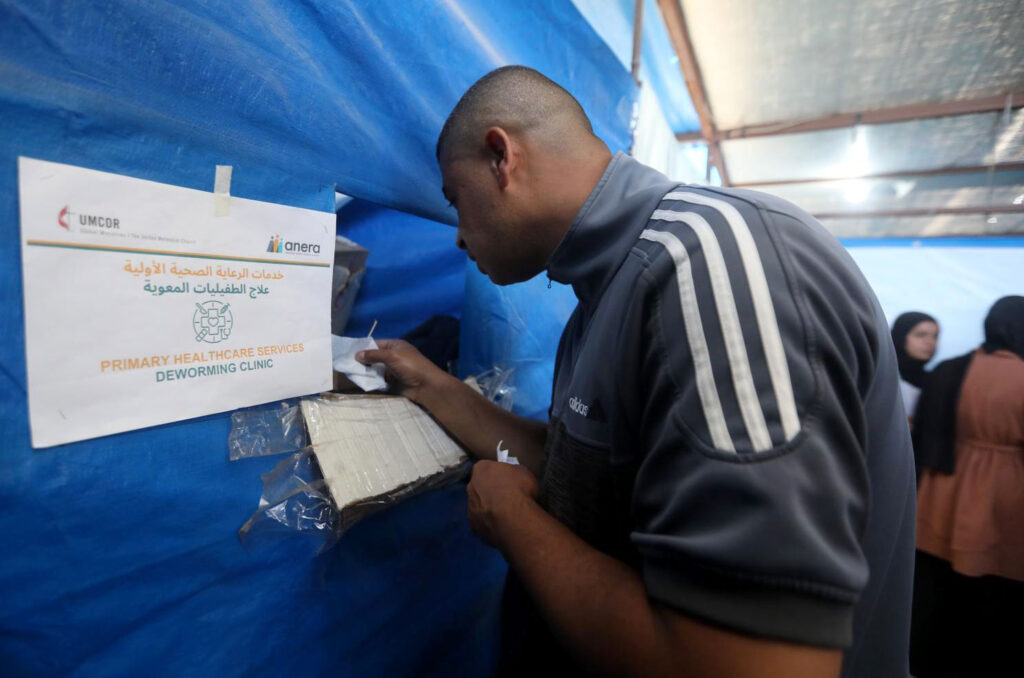

Fighting parasites to protect the youngest lives with support from UMCOR

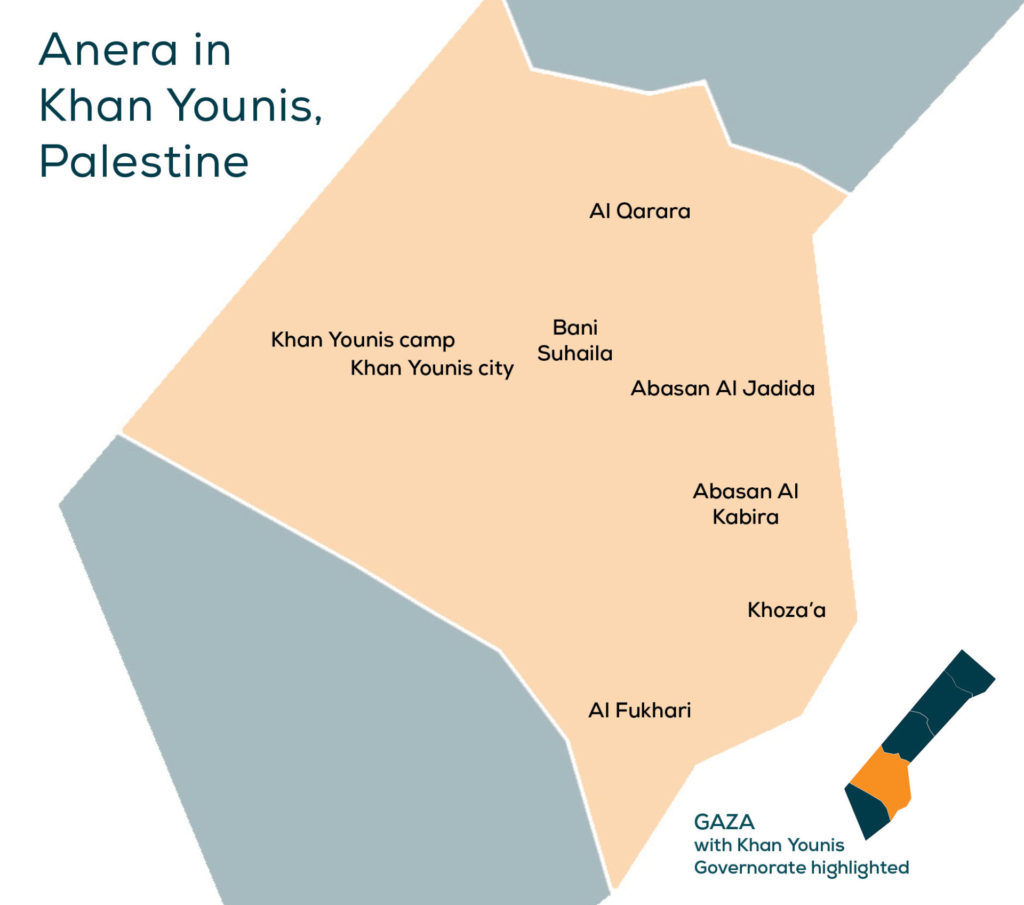

In the crowded streets of Mawasi, Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip — lined with vendors and passersby — Khaled, 34, walked wearily with his two pale-faced children.

Khaled, a father of three, was displaced from the Zeitoun neighborhood in eastern Gaza City a year and a half ago. He has not returned home, even after the declaration of the ceasefire last January.

“I haven’t gone back. My house is completely destroyed. There’s nothing to return to,” Khaled says in a choked voice as he looks at his children — Wael (6), Ahmad (4) — while sitting on a plastic chair in Anera’s clinic waiting room.

Life inside the tent is nothing like the life Khaled once knew in Gaza. Like thousands of other displaced families living in makeshift shelters, nothing in the tent is stable except exhaustion, and nothing grows but suffering.

“It’s a tragic life. Maybe you can handle tent life for a month — but not for a year and a half,” he says. “We Gazans are used to clean, organized homes. But here, everything is upside down.”

"It’s a tragic life. Maybe you can handle tent life for a month — but not for a year and a half.”

White Spots and Silent Pain

The days pass heavily for the family. Life is inhumane living in a tent amid bombing, fear, sealed borders, and food shortages. But for Khaled, he only felt real panic when he noticed changes in his children’s skin tone.

“White spots appeared on their faces. Their skin looked different. My wife and I didn’t understand what was happening,” he recalls. “There was no fever or stomach pain. It was confusing.”

A few days earlier, while walking down the street to find basic groceries for his children, Khaled spotted Anera’s clinic. Curious, he now inquired about it and decided to bring his children in for a medical check-up.

He received an initial diagnosis at Anera’s health clinic, and the children were referred to the deworming clinic, supported by UMCOR, that treats intestinal parasites.

"White spots appeared on their faces. Their skin looked different. My wife and I didn’t understand what was happening.”

“The doctor referred us to the lab, where they conducted tests. It turned out they had intestinal parasites,” Khaled says, holding two boxes of medicine in his hands.

“The doctor was very cooperative. They gave us the medicine free of charge. Thank God,” he adds with a smile of relief.

But as Khaled explains, the story didn’t end there — it had just begun.

The Environment Is the Disease

The intestinal worms and parasites, he explains, didn’t come from nowhere.

“There’s no proper hygiene in the tent, no matter how hard you try. The water is dirty and full of sand. Even when I wash the kids after using the toilet, it’s not like being at home. The water isn’t clean.”

With no proper sanitation or safe water, maintaining cleanliness has become nearly impossible.

“There’s no proper hygiene in the tent, no matter how hard you try."

Even the Medical Staff Are Infected

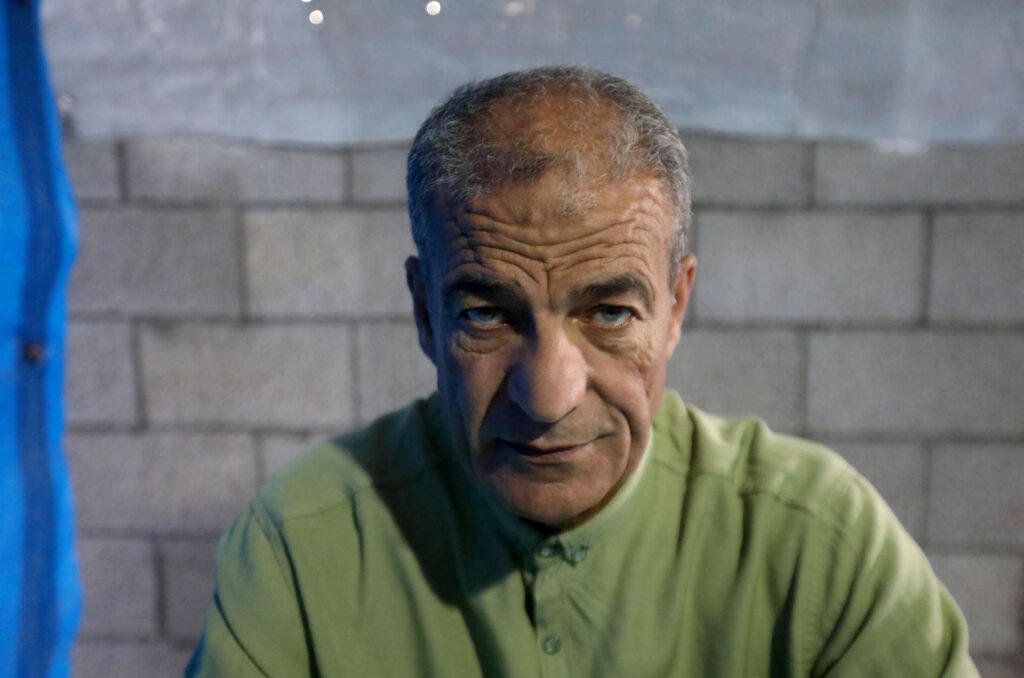

Omar Abu Shaqra, a physician specializing in pediatrics and internal medicine who has worked at Anera’s clinic for three months, describes the health situation in one word: “catastrophic.”

“Intestinal parasites are extremely widespread in Gaza,” he says from inside the clinic. “Not just among children — even medical staff have gotten sick. Everyone is at risk.”

“The causes are clear: contaminated water, lack of hygiene, overcrowding due to displacement, and environmental pollution, including garbage piling up everywhere.”

Abu Shaqra says people collect water in unclean containers with no oversight, and the food quality is poor due to a heavy reliance on unhealthy canned goods.

“People fill water in dirty gallons and bottles. There’s no supervision. We try to raise awareness about hygiene, but it’s extremely difficult under these conditions.

“The health situation is dire, especially with severe shortages of essential medications and supplies. Many key medicines are simply unavailable.

“But we’ve been able to manage thanks to donations — including those from UMCOR to Anera. These contributions provided essential antiparasitic medications and helped us treat dozens of cases that would have otherwise deteriorated.”

Abu Shaqra recalls treating an infant only four months old who was diagnosed with cystic amoebiasis — a condition rarely seen in children that young.

“It usually affects adults, but the environment these babies are living in is so toxic — no clean water, no proper toilets, no way to wash produce. The family simply cannot clean their food properly before feeding it to the child.”

He notes that pinworms are also rapidly spreading among families.

“If one child is infected, we treat the whole family, because chances are they’re all infected without knowing it. Treating this is like solving a multi-layered puzzle.”

The hardest part, he says, is that people get reinfected. “We often see patients return after completing two-week treatment courses, still infected. It’s not that the medicine failed—it’s the toxic environment they return to.”

The doctor explains that most infections start with noticeable skin or digestive symptoms.

“Mothers come in saying they see white spots on the face, or that their kids are constantly having stomach aches or visible worms. Some children say they eat but never feel full, or they complain of itching after using the toilet. During examination, we often find pinworms visible around the anal area.

“The infected child is usually weak, constantly crying, and lacks focus. We rely on physical exams when lab results don’t clearly show the parasite—because in many cases, the worms are visible to the naked eye.”

A Rapidly Spreading Threat

When he started, Abu Shaqra used to see three to four cases per day. Now he sees 50 to 60.

“It’s escalating fast. Infections are spreading rapidly due to dirty water, lack of soap, and no proper cleaning tools. It’s a disaster.”

Treatment typically involves albendazole — known locally as “Vermox."

“We give young children half a tablet, then repeat the dose after 10 to 15 days. Adults take a full tablet and repeat after the same interval.

“The treatment lasts two weeks to a month. But the issue isn’t the treatment—it’s the environment, which keeps reinfecting people.”

Beyond Worms… Hunger

On top of all this, Khaled worries not only about his children’s health but their hunger.

“Food is a huge issue. Local aid kitchens in our area shut down. Canned food is running out. Even bad-quality food is no longer available.”

With no crossings open to permit food into Gaza, prices have skyrocketed. “It’s madness. The average family can’t afford to buy basics anymore.”

“My kids have been wronged,” he adds. “Life here is not fit for children — or adults. We’ve entered a state of famine.

“We plead with the world to open the borders. All we want is compassion — for our children, our pregnant women, our wounded, for everyone.”

A Clinic Saving Lives

Despite these overwhelming challenges, Anera’s clinic has stood out as one of the few efforts making a tangible difference.

With the support of organizations like UMCOR, Anera has been able to supply medication, offer free treatment, and relieve pressure on Gaza’s collapsing health system. But it's an uphill battle until sanitations systems can be restored.

“Medicine alone is not enough," Abu Shaqra warns. "We need a clean environment. Every day that the war continues and living conditions worsen, the number of infections grows.”

“Even the medicine we do have is now at risk of running out, especially with aid blocked from entering for over two months.”